Soldier – a prologue.

April 10, 2010

|

“Soldier” – a Hesirion fragment.

A cloud, the shape of a river bloated corpse, drifted lazily across the evening sky. Far below, its sluggish progress was noticed and as quickly dismissed by a ragged cloaked soldier. Short well made boots unfurnished with spurs, unusual for this country, tramped the beaten earth road. Loose fitting hosen of black buckskin, strapped to the knee in the fashion of the northlander mercenaries, again rare for this country, showed a thick layer of dry dust from the sun blasted soil. His leg wear alone would have signalled him as a stranger to any of the watchful here in the heart of Al-Khetir Province. Not a tall man but broad, he wore beneath his cloak a fine, if well used coat of mail that covered his chest, arms and thighs; fastened at the waist by a thick sword belt from which hung a plain scabbard with simple brass fittings. The mail, broken and patched in places, revealed a black padded and polished gambeson of leather underneath. His left arm and shoulder were further protected by a mismatched set of plate. His left hand, sheathed in a battered gauntlet the quality of which could still be seen from the remaining silver inlay, rested upon the heavy unfussy pommel of his long straight sword. Well balanced, and with its blade honed on both sides to a razors edge it was a butcher’s tool, so unlike the dress swords worn by most of Al-Khetir’s courtiers. The coif of his mail coat hung loose over the gathered hood of his mud spattered black cloak, the leather fastening straps flapping in the dying wind about a palm sized brazen clasp, fashioned in the shape of a raven. His head, bare of a helmet or cap, showed his long salt and pepper hair, a gathering of which was shaped into the topknot so favoured by the tribesmen of the Cuimmi and the Whiddermen of the sleet whipped North. The rest was gathered loosely below the nape into an unruly plait that hung to his waist. Unshaven, broken nosed and lined with half a dozen scars, some of which cut into his beard, his face was not that of a man used to a soft existence. Yet for all that he was not an ugly man. His grey-green eyes showed wit and intellect, and his few friends, scattered as they were to the far north and east, would no doubt vouch that on the rare occasions that he chose to smile it belied a warmth of character that softened his usual feral looks. Across his back was slung a plain leather bag, a canvas sack filled with arrows and a painted black war bow that from bone tip to bone tip measured a full hands breadth taller than its owner, the bone knocks again wrought into the shape of ravens. His alien appearance was finished with a loose slung belt hanging from his left shoulder where it crossed his chest and was fixed to the sword belt with a brass fitting. From this were hung a simple leather covered buckler, battered and bent, seemingly having been used as a punching weapon as much as a defence against a sword; and two sheaths. The first of these housed a common bone handled knife, typical of a soldier, and used for his everyday needs of cutting hempen rope, trimming leather straps and eating his food. The second concealed a ten inch blade of the finest steel, surmounted with a sharpened U-shaped guard designed not only to trap an opponent’s sword blade, but to puncture their flesh. The unusual dagger’s ivory handle was exquisitely carved into the likeness of two winged serpents entwined, whether as lovers or bitter foes it was impossible to tell. Every so often as he marched the soldier would reach his closed right hand and nudge the buckler as if to try and cover the dragon handled blade, but the action of his walking would invariably cause it to reappear. His right hand, itself sheathed in a black leather glove that reached half way to his mail-covered elbow, never unclenched, gripped fast around an object more curious and exotic than the soldier and the dragon wrought knife put together. For though he didn’t know it, and though he would not have had the words in any of the dozen languages that that he could speak, he held in his fist the silver coloured handset of a mobile telecommunication device. Somewhere above, the corpse shaped cloud slowly transformed itself into the likeness of a sprinting hare and continued its journey west, while far below a ragged cloaked soldier walked south towards a city. |

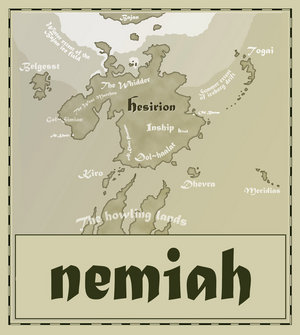

Nemiah

April 10, 2010

”Nemiah” – a Hesirion fragment.

Two gliding shadows, hot to the touch as they caressed the salt-glass sand, mingled and fused with the cooler unmoving shade of a tall Levaan Palm. The tree’s twisting stems marked the edges of the spreading fingers of the great Inship Desert; sun burned fingers that had long ago begun to stretch and claw their way into the cooler, ocean quenched lands of the Dol-Haalat, and here, at the north-western edge of the land of Hirad.

Dadengo, the sun, not quite halfway through his journey across the cloudless lapis lazuli ocean that served as the Haradi-Inship sky, shone as only a god could; and the heat of his love for this land would only increase as noon approached. Below, a pair of tattooed lizards danced a foot-cooling dance while keeping at least one of their rotating eyes on the interlopers.

Of the two owners of the now motionless shadows, the most immediately striking was the tall graceful woman. Poised like an ancient bronze statue, gripping in her left hand a slender yet formidable looking hunting spear tipped with a recently bloodied khenn-stone blade; unmoving, she watched the quivering desert horizon.

Her hair, the colour of rusted iron, was cropped short in the tradition of the Tingaket, and criss-crossed with finely shaven lines leaving just two long braids in front of her ears. The braids had been weighted and adorned with silver wire and salt-glass beads, some of which were fashioned into the snarling shapes of totemic animals.

She was clothed in the, again traditional Gerbohn of the Tingaket woman. A simple garment made from a long strip of intricately patterned silk wound around the waist and drawn across the breasts then wrapped about the throat. Her outfit was completed with a sheathed, bone handled knife, and a thick water-skin hanging from her hunting girdle.

Her obvious, practiced power as a warrior adding to the chance beauty of her person, she cut a stunning silhouette against the bleached desert sky.

Her companion, a young girl, so plainly her daughter that a blind man would have known it, carried nothing but the garment she wore and the overwhelming weight of her fears of what the next hours might bring.

Beside them on the glistening, burning ground was the trussed carcass of a young Kifrit, a short but stocky breed of antelope that haunted the great desert’s borders, the bloody spear wound in its flank already dried in the heat. Resting against the calf’s corpse and looking like its stunted sibling was a small Kifrit-skin bag, from the open top of which there gleamed the silver rim of a small bowl.

Nemiah and her mother had spent the previous two nights at the Holari-kel-Abi, a small but verdant oasis, a quarter-days walk from their village. A century before the oasis had been a regular way-station for the nomadic peoples of the southern Inship and an important stop on the now abandoned Togai Spice Road that ran from the ports at Old Bhutan on the Eastern seaboard to Al-Khetir in the West. Then, following the Corsair Wars when the great ships had been brought from Gol-Simion, the long and arduous journey overland was rejected in favour of the faster, and more profitable routes of the trade fleets. In just a few years Holari-kel-Abi, untended and forgotten, had become a shrinking puddle beneath the ruin of a stone watchtower, half-hidden beneath a tangled mass of kaup grass, rhishi vines and spindly Levaan.

Then the women had returned.

Slowly the little patch of straggly vegetation and water had been transformed into a garden. Even the stone skeleton of the watchtower had taken on an air of ancient beauty.

It was as the first sliver of light had showed on the eastern horizon that Nemiah and her mother had emerged from the tower, roused from their simple but comfortable beds of thick moss and palm fronds to a breakfast of nothing but moon-chilled water. From there they had continued their journey westward through the increasing heat of the day to arrive here at this beautiful, burning, dread, sacred place.

Nemiah’s feet were sore, her legs ached from the long morning’s walk, her mouth was dry and she had become breathless trying to keep up with the long but easy strides of her mother. Her mother? The last two nights had revealed more about this tall proud woman than had the thirteen years in which they had shared each other’s home. Her head was reeling. Just three days ago this warrior huntress standing just a hands span from her had been nothing of the sort, just a simple, quiet, loving wife to her husband, and tender patient nursemaid to Nemiah and her siblings. Then suddenly in the blink of an eye, a new creature had emerged from the soft warm comfort of her mother’s frame. A creature that could find its way in the pitch dark, track and spear a nimble Kifrit – at a distance even her brothers would have been impressed by – and she could read.

Nemiah’s mother could read!

Holari-kel-Abi’s watchtower had been built long ago. The craftsmen who had shaped the stones that so neatly interlocked to form the strong bastion of the tower itself had also shaped the monoliths and steles that where scattered amongst the ruins that surrounded the oasis. Nemiah had been led on that first day to the largest of the stones, and her mother, wiping away the wind blown sand from its face, had traced her fingertips over the rows of arrow head markings and glyphs carved by a forgotten people over half a millennia before. Then lifting her hand back to the top of the stele she had retraced the lines, this time reading aloud the words hidden within the carefully made marks.

Through her mother the stones then began to give up their accounts of a great sea borne empire. An Empire that had at one time had stretched from the edges of the frozen North to the now uncharted South, and held dominion from sunrise to sunset no matter where on the great continent of Hesirion you stood.

Nemiah heard the tales of the hero-kings of the Glass-Lion Empire and the slaying of their enemies, the defeat of whole nations, and the great lists of tribute and slaves that were taken. On the second day Nemiah’s mother had led her from stone to stone, each new carving shedding light on the rise and fall of a long dead people.

One stone, inset within the wall at the base of the tower itself, told of its construction. How the stones had been brought by great oared ships from beyond The Howling Lands, then dragged overland on great sleds pulled by golden horned oxen to this place, then honed and shaped and set upon each other. And how long ago, from the very top of the tower, a great fire had blazed. A fire tended night and day, year in year out, so that it never dimmed.

The morning’s journey and even the hunting of the Kifrit had been made in silence. The last hour, with her mother doing nothing but staring into the heart of the desert had also passed without a word being spoken. There had been no instruction not to speak, but Nemiah had simply known that it was expected of her. The events of the previous days had become ritualised, something sacred was taking place, and she had tried to behave accordingly.

Nemiah’s stomach growled and whined like a neglected puppy and she felt ashamed.

Then the increasing heat of the morning had brought with it another surprise.

The shadow-children.

For there, at the edge of her vision, where the desert sand turned to shimmering glass and met the white hot edge of the desert sky, a group of shadowy figures moved, and slowly they came closer.

“Can you hear them?” her mother said suddenly.

Nemiah eyes widened.

“It means She is coming”, her mother said turning to Nemiah and smiling. “They are her heralds, the girl-children of the Tingaket who never passed into womanhood.”

Nemiah did not know who the “She” spoken of was, and at this precise moment did not care, she simply stared open mouthed, watching the mirage children dance and play in the rippling heat haze.

“I can hear them”, she said at last, her voice barely above a whisper.

“And what do they say?”

Her mother had crouched down, and sat on her heels, her free hand resting on her daughter’s arm.

“They… they are calling my name.”

She sounded astonished.

“They want me to go to them… to play with them.”

“And do you want to?”

Her mother stared down at the ground between her feet.

“I…”

Nemiah paused and looked down at her mother who suddenly resembled her old soft self. Brushing her hand across her mother’s hair and returning her gaze to the rippling shadows of the children, she thought for a moment.

“No. I thought I did, but there is something else I must do isn’t there? I can feel it pulling at me like the changing of the tide in the Bengshai River.”

Her mother smiled and stood. Then leaning forward kissed her daughter gently upon her brow.

“Come, we have one last thing to do before we return.”

Nemiah’s heart sank.

………………..

They both sat cross-legged beneath the welcome shade of the wide Levaan leaves. About them, drawn in the sand by her mother using her spear’s blood stained blade, was a wide crude circle. Placed carefully on the ground between them were the spear and the silver bowl along with the final contents of the skin bag. Namely, an elaborately carved long bladed knife, the like of which Nemiah had never seen before, and a heavy golden coin that she had found and presented to her mother on their last night at Holari-kel-Abi.

Once her mother was happy with the arrangement of the objects, she took a deep breath and closed her eyes. Then just as Nemiah thought she might have fallen into a meditative sleep, she spoke.

“You will learn as you get older that truth is like a great country with disputed borders, ever changing, and wholly dependant on the person who bears witness to it, who is on the throne, and on which side of the drifting border they are standing. Some things are true. Some things become true. Others yet have always been true, and will be until the death of the world.”

Her eyes opened and she fixed her daughter with a stare.

“One of these last truths was told to me here in this very place by your grandmother. Your grandmother had in her turn sat here and learnt it from her mother, and her mother from her mother and so on for over a thousand generations.”

Looking down at the objects she spoke with such a serious conviction that it made Nemiah tremble.

“It is the great secret truth of the Tingaket women, for just as the men folk have their stories and secrets, we have ours,” then with a smile, “It is just that our stories are true.”

With that she closed her eyes and began.

…“And so it was, that long ago, before the world was wrought as it is, before the rise of the Glass-Lion Kings, before even the gods of the Tingaket were born and risen to greatness, the earth beneath our feet was home to other creatures, the first born of the Gods. Some were just little gods, some not so little, and others great indeed, and there in the turmoil at the beginning of the world they fought and loved, created, destroyed and died. Others still were creatures of such might and power that they were unafraid and untouched by Death. These, my daughter, were the Parcchaizi. The great and immortal dragons that shaped the world with fire before their throats grew cold…”

Nemiah sighed, and her mother’s voice stopped. Embarrassed, Nemiah felt the heat rise to her chest and face and she looked down. She had expected to be chided for the interruption and was surprised when her mother asked her softly.

“What is it Nemiah?”

“I… I have heard this story” she said without looking up.

“This story?”

“ I believe so ma Eveh” Nemiah replied.

“Hmm? And where do you believe you heard it?”

“From Hebbe.” She said slowly, then looking at her mothers almost amused face, blurted.

“He told me the story when he came back from his cutting last summer. He said how Tingak was born into the dark world and subdued the dragon kings and used their fire to defeat his enemies, and to shape the world to his will and…”

Her mother held up a hand stopping Nemiah’s abridgement of Hebbe’s tale, and causing her daughter to blush and drop her eyes once more.

“It would seem to me”, she said after a moment’s silence. “…that the secret stories of men, as foolish as they might be, would remain more of a secret if they were told to someone other than men.”

Nemiah would normally have laughed at he mothers joke, but the fear that had been with her since they had set out on this journey, a fear that had become swollen as the silent morning had passed, had transformed into a choking lump in her throat. Instead she just raised her face to look at her mother, tears welling in her bright eyes but not yet spilling, and asked quietly.

“Am I to take the cutting?”

“What?”

Her mother, so prepared to ease her daughter into womanhood through the rituals that had been passed down from each generation of Tingaket woman to the next, had been shocked by the question.

Tears were now loose on Nemiah’s cheeks and she reached over to grasp her mother’s hands imploringly.

“It’s just that Hebbe and Mischa said…”

“Wait, wait… Nemiah”, said her mother, shaking off her daughters grip and leaning over to stroke her distraught face.

“So that is what this has been about. You have been listening to your brother’s teasing again…”

Sighing with relief, and letting out a little laugh, she took Nemiah’s trembling fingers into her hands.

“I had wondered why you had been so quiet at the oasis, so distracted.”

Then looking long into her daughter’s eyes she spoke.

“Nemiah… there will be no cutting for you. We are fortunate that the men of the Tingaket like their women whole…”

“But the Farouk… Hebbe says…”

“The Farouk are a godless, foul, and barbaric people and as such have been hounded and chased to huddle by the Togai Sea by our people. It is true they treat their women worse than they treat their animals, and it is also true that our men once prayed in their temples and did as they did, but we have been sundered from the Farouk for over five hundred years. We and our men are not the Farouk.” She shook her daughter’s hands in encouragement.

“Are we?”

“But Hebbe…”

“Are we?”

She had interrupted her daughter more sternly than she had wished and the shock showed on Nemiah’s face.

“No ma Eveh”

“That is right, and so there will be no cutting, not today nor any other day, not for you or any other daughter of the Tingaket. And as to your brother’s story of Tingak’s making of the world, you can forget that also. For the story I will tell you today will be the truth, a truth about who you are, and one you will tell your own daughters one day.”

Then letting go of Nemiah’s hand and closing her eyes once more she asked.

“May I continue?”

“Yes ma Eveh.”

Nemiah’s sense of relief was so great she didn’t know whether to laugh or cry all the more, she had been in fear of her brother’s story of the mutilation of the Farouk women for weeks now, ever since she had become aware that this ritual journey approached. But he had lied.

He had become a man last summer having been taken to the mountain hunting grounds to the south of Hirad and there been circumcised.

Still sore from his ordeal he had then sat around the campfires of the hunting party and heard the various stories that the men told each other on such occasions. Some had been tales of the old heroes of the tribe, others about the ancient wisdom of the Tingaket hunters. Some had been the secret tales of the men, and here he had heard the tale of “Tingak and the Birth of the World” as the men tell it. He had heard the stories of “Belthusa and the Dream Wine”, “The Monkey and the Crocodile King”, and “The City of the Jadebird”.

Then as the night wore on, and the honey beer brought to the hunt by the older men began to take effect, he had begun to hear the more vulgar tales and jokes of the Tingaket men. “Tokemesh the Fool and his New Bride”, “What Hitanni Saw” and the frightening “N’gagi and the woman with Teeth Below”.

He had returned home, uncomfortable but proud to be considered a man, to torment his sister with yet other tales he had heard, tales of the Farouk and the suffering of their women. He would pay for that twice no doubt, once at the hands of his mother and again when his sister had the tranquility of mind to pursue her own appropriate and delicious revenge.

Yet as the day wore on Nemiah forgot all about her brother, and became enraptured by the tale her mother told. The story of a goddess named Litteveh, The Great Mother. A goddess who was born from the heat at the heart of the world, her beauty forged like a blade that cut a swathe through the ranks of the gods and dragon-kings alike, until they could not help but fight for, and over her.

“Now some say that the dragons did not die, that some still sleep beneath the world, and it is their writhing dreams of the goddess that cause the sliding lands and the shaking of the earth. Others, many sailors from the southern seas among them, still maintain that they continue to walk the earth far to the south beyond the haunted isles and the Howling Lands. Yet these are not the true dragons of the beginning of the world, merely the blind and unthinking whelps of dragons and other beasts of the great dark, and bear little likeness to their sires of old, for the Dragon-Kings were great creatures indeed.”

And as her mother’s voice swept around her and over her, Nemiah sat wide eyed, and she heard how the goddess one day saw a high king of the great Dragons kill one of the little gods over the cooling sea, and how he ate its heart, revealing the secret of their immortality. She heard how the goddess set her snares, turning Dragon-King against Dragon-King one by one, luring them to their deaths with her beauty and at last feeding on their hearts herself until just one remained, the most powerful lord of the skies, the great and terrible Bessat.

“And so, as immortal king and queen they ruled over the burning earth and were worshipped by beasts and gods alike.”

“But even Immortals grow weary of the world, and Bessat, kinless, the last of the great Dragon-Kings, one day slipped away and left Litteveh to herself.”

“Her grief was great, too great; a wracking endless pain growing inside her. And she too wanted to leave the world behind; seeking death. But leave it she could not, for she had fed upon the hearts of the last immortals, and though she succeeded in destroying her body, her soul lived on, and she would find herself reborn, again and again and again.”

Nemiah’s mother opened her eyes and looked at her daughter.

“A wise old woman of our people once said that “some things leave their life and enter into death, some things simply stop living… and yet there are others that will choose to become something else still. Litteveh it would seem was just such a thing.”

“Yet each time she was reborn she would appear in a different form, always remembering the time before. Sometimes she would live for many years before remembering, other times she would recall everything from the start; but always she would be reborn.”

“And so one day, to help her remember, she walked into the drying desert and came to the shade of a Levaan Palm, and here,… right here, on this very spot, so it is told, she created the Daneshi. Women in her likeness, who are here to remind her, preserve and serve her, serving no other. And even though they have mingled with the men of the earth and sit beneath their men’s idols and their many temples raised up to honour the younger gods, the Daneshi remain true to Litteveh.”

A look of dawning realisation passed over Nemiah’s face and her mother nodded.

“That is our secret truth my daughter. For the women of the Tingaket are the daughters of the Daneshi. And though other men and women in the lands of the world know the Goddess, some of them in the south as Nett-hamesh; some to the north as Allder, and Shorae, she is and always will be Litteveh, The Great Mother, and we were made by her to serve her.”

“Nemiah… you have dragon’s blood in your veins and your soul has walked this earth many times before. For just as Litteveh’s soul is reborn and reborn again, so are the souls of the Daneshi passed from one woman to another. It is why we later feel the weight of the years so greatly. For our immortal souls are burdened with the suffering and pains of a thousand lives, and the heart rending grief of a Goddess.”

Nemiah thought about it for a moment and she knew in her heart it was true, and yet she had a question.

“But what of our men? Do not they have a soul?”

Her mother nodded, smiling sadly.

“Yes, they have souls, just as all creatures do, but a man’s soul does not pass from one to another, but is taken into true death and sees not the earth again, and each newborn man-child is granted his soul afresh.”

“Some say that this is why they act like children throughout their lives; because their souls are so young.”

Again Nemiah saw the sense in this and, suddenly felt a wellspring of feeling within her as she realised the enormity of the secret, that and the burden that it brought with it. For each woman who heard the story would then never tell it again, not until the day she passed it on to her own daughters.

“Come now”, her mother said and reached behind her for the water-skin slung at her back.”

“Dadengo has neared his journey’s end for today and we still have to make it back to the watchtower; but first I must show you something.”

Unstopping the water-skin, she poured some into the silver bowl. Then offering it to her daughter she urged.

“Take another look”

Her mother had done this before. That had been on their first night at Holari-ken-Abi, and she had shown Nemiah her reflection in the moon-lit water held by the beautiful silver bowl. When asked what she saw she had complained to her mother that her hair was patchy where the Henna had not taken and that she didn’t like her nose. It had been the reflections of a young girl caught up in the worries of her friends about their hair and their fears that the village boys would not find them attractive enough at the high summer festival. Her mother had laughed and drained the bowl and dried it before placing it back in the Kifrit-skin bag.

This time as Nemiah looked into the rippling water she saw only the strong features of her mother showing through her thinning face and the eyes of a huntress, and behind the eyes. With a start she gasped a name…

“Litteveh!”

Night had fallen and Peluma, the moon, bathed the desert in her gentle half-light as Nemiah and her mother approached the ancient stones that guarded the oasis. For more than half a candle mark they had heard the sounds of music and laughter curling over the desert air towards them. Then suddenly, passing over the gentle ridge of a low dune they could see the flickering shadows of dancing figures in the night, for someone had lit a great fire in the top of the watchtower.

That night Nemiah joined in the dancing of the Tingaket women as they celebrated the latest addition to their covenant with the goddess. And there among the fires of the Daneshi, and through the haze brought on by the flowing Herap wine, Nemiah swore she caught a glimpse of a woman she has never seen at the village. Nor the river-market near the Port Roads. A woman built like her warrior-poised mother, and with a face of a goddess, a goddess who killed the last great dragons…

and she smiled.

Fynn

March 26, 2010

“Fynn” – a Hesirion fragment.

Light glinted along the curved metal edge of the Khotai as it reached the zenith of its motion. The blade, two and a-half cubits in length and three fingers broad, seemed to hang there weightless in the thickening air. Until, after what seemed like an age, the Khotai, swung by the powerful arm of the Dhejenim warrior, was brought back down with such force that it would have severed the head of a bull.

Fynn, debris scraping his eyes, felt the blade slash by and the sharp pull as it bit through his hair. He had rolled to his right instinctively, and it had saved him. Blind, he reached to where he thought his weapon had fallen, and found nothing. The Dhejenim grunted and Fynn through their entangled legs felt his assailant straighten to strike again.

To Fynn time seemed to have slowed almost to a standstill, the reflex like parries and thrusts, defences and counter attacks of the last two minutes had stretched into a languid slow dance, as if the warriors fought in deep water. His eyes, undone by a hand full of dust and ground eggshell, would not recover fully for an hour at least, and almost immediately his other senses had shifted and swelled to fill the vacuum of his awareness.

With careful precision he shifted his weight, his left foot moving to encircle the flexing leg of his enemy. At the same time he raised his right leg into the air and sliding it like a serpent across the oblivious Dhejenim’s body, found purchase beneath the heavy girdle of leather and horn that supported the Khotai’s sheath.

Fynn then did the impossible.

……………

Ghozhai-han, had killed two men today already, this unarmed and un-armoured stripling would be his third. He just wished the eel would stay still. He had to grant the boy his speed. How he had avoided the Khotai’s killing stroke the Dhejenim could not fathom. But the pocket full of powder had done its job and he knew his opponent was as blind and helpless as a new born kitten. Raising himself up to his full height, a full head above any other warrior in the personal guard of Bholmenn-Khett; all of whom were tall men, he raised his deadly blade for the final time.

To Ghozai-han what happened next felt peculiarly like he had been picked up and then laid gently down again, like a child being laid in its cot by a careful mother. To Fynn it was a single soft stepping forward. While to the stunned spectators within the makeshift arena it seemed as if the two warriors, one prone the other standing above him victorious, had simply been turned ninety degrees, as if by an interventionist god as a man might turn the hands of a clock.

……………

As his body lifted from the ground, propelled upward by the falling motion of the Dhejenim, Fynn raised his hands to intercept the moving sword arm that still carried the blade toward him; the force of the blow lessened by Ghozai-han’s disorientation.

Taking the upper part of the Khotai’s grip in his right hand, Fynn twisted his enemy’s wrist and hand sharply with his left, removing one from the other.

……………

Later, as they huddled and discussed the fight in the shadows of a grim dockside tavern or the oil-lit back row of another baiting pit of Hereborn, those that had been in the crowd claimed the whole shift of power had seemed to have been a single, almost ballet-like movement.

Even those who could claim prowess with a blade and a working knowledge of hand-to-hand violence for themselves, and of those there had been several, grunted their approval and admiration.

For at the apparent moment of his death, and in one flowing movement, the boy had raised himself up, and blocking a deadly sword blow, had pushed his assailant flat. Turned, with his opponent’s sword now in his own hands, and using the long Khotia blade like a scythe had removed the head of the fully armoured Dhejenim warrior at his feet.

What came next happened just as swiftly.

……………

Fynn, could feel the silence that followed his victory, it pushed up against him, abrasive and predatory. His eyes, still blind, felt like hot coals, tears streamed down his face, and in the half-light of the baiting pit he was suddenly aware of a movement behind him. Turning towards the threat he struck out with the blood stained blade at the nearest of a group of blurred shadows.

……………

Bholmenn-Khett, Pharhai of Eigermon, had been applauding his champion as he raised the Khotai for the final blow, and had turned to face his latest bride who sat behind him in the silk draped seats separate from the common stalls. He had hoped that this bloodletting might go as far as to stir up her own blood. Perhaps even engender a vicarious respect for her new and eager husband, anything but the cold venomous stillness that he had experienced the last two nights. Yet as he looked at her and watched her half-lowered eyes widen and her beautiful but melancholy face transform into a picture of joy, Bholmenn-Khett could not help notice the look of horror on the faces of the rest of his entourage.

His attention swung back to the pit at almost the exact moment the great blade, now impossibly in the hands of the ragged pirate whelp, struck the throat of his prize gladiator.

He was incredulous, a disbelieving laugh transformed into red-faced anger in his throat and he choked, spittle frothing onto his chin and splashing onto the dry floor of the arena.

Staggering to his feet, his eyes bulging, his whole face a mask of hate, Bholmenn-Khett, began to draw the short Hensai blade from the silk-wrapped scabbard worn across his waist, launching himself toward the still blind Fynn, several of his bodyguard at his heels.

……………

It was a matter of honour as well as tradition that the Dhejenim keep the blades of their Khotai razor sharp, and a smith or a travelling whetstone-man who knew how to keep these all but sacred blades in this ideal condition where prized indeed. Ghozai-han had gone as far as to employ a particularly skilled and favoured smith into his own small retinue.

The blades, traditionally used as one would a cutlass and designed for heavy slashing strokes, were usually only sharpened on one side. Yet following a display of arms at a gaudy tournament in Gol-Simion, Ghozai-han had adapted his fighting style to include several straight thrusts. He had then instructed his servant to grind and sharpen the first few finger breadths of the upper edge to create a deadly lance-like point that, with enough strength, could be forced through a coat of mail or lacquered shell armour, as well as the heavy gambeson beneath.

……………

It was this blade, so sharpened, that punched through the breast-bone of the still incredulous Pharhai to protrude a foot from the expensive fur lined cloak at his back.

Hundreds of semi-precious beads and tiny cut-glass masks tumbled to the floor, freed from several long necklaces that garlanded the throat of Bohlmenn-Khett by the razor edged Khotai.

The first of the small yet ingeniously shaped masks to hit the floor was crushed and cracked beneath the heavy boot of the nearest bodyguard; while at almost exactly the same instant one of the falling beads was shattered by a steel-tipped arrowhead.

Then, as if pulled from behind with ropes, the armoured bodyguards where whipped backwards, each with at least two black-fletched arrows buried deep in their bodies.

The last of the arrows struck Bohlmenn-Khett in the chest and neck, all this still just moments after Fynn’s sword had struck home, jerking the Pharai’s dying body backwards so hard that it was pulled free of the long blade.

Finally the room was still.

……………

……………

“Karl?”

Flynn’s hopeful question hung in the air with the dust.

“Aye, and some of the lads.”

At least a dozen dark cloaked archers stood in the shadows at the rear of the stands behind Fynn. In their midst was a dark shape that stood at least as tall as the dead Dhejenim.

“I can’t see Karl… the bastard used ground eggshell, and…”

Fynn’s words were cut short by the sound of several longbow cords being stretched.

“What?”

Fynn turned his head left and right trying to locate the new threat. Then suddenly he was aware of a smell so out of place in a baiting-pit, not a smell, a fragrance.

Bergormine and Esterwood.

……………

The young widow of the Pharai stepped slowly down from her bench, her eyes never leaving the face of the young warrior who had unwittingly freed her from the unwanted attentions of her ogre of a husband. Her two handmaidens squeaked in fear and reached for her as if to stop her. Ignoring them she stepped into the pit.

The walk from the silk strewn bench to the body of her husband could not have been more than nine feet, yet it seemed to her that it took forever to close the distance.

……………

Fynn, trapped in the pain scraped dark, and reaching out with his senses recalled a fleeting glimpse of a beautiful young girl seated behind a wealthy looking merchant type. It had been as he was being led into the small arena behind The Candlehand Inn.

This fragrance had to be her he thought. Standing so close now he could feel her breathing.

What in hell did she want?

He suddenly remembered his sword arm, still outstretched. The ache in his shoulder now acutely uncomfortable he let the sword arm fall, the sudden movement making the girl gasp.

The rest of the crowd, so quickly cowed by the sudden violence toward none combatants, were beginning to regain their bravado, yet another unified creak from the black bows again urged them to silence.

“Fynn, come on. One of these bastards is bound to have sent for the harbour watch, we need to get clear… at least to a different ale-pit.”

“Just… just a moment Karl… I…”

Never taking her eyes from her ragged pirate saviour the girl bent down to her husband’s body. Taking the Hensai, still half in and half out of it’s scabbard, she lifted the hem of her husband’s expensive tunic, gold thread work still showing through the damp dark stain that continued to spread. Then cutting the heavy purse free and leaving the blade on the ground beside her husband’s body, she stood; taking the young pirates hand she placed the purse in his palm, closing his fingers slowly around it.

Fynn smiled, and the girl smiled back though Fynn could not see it. It was a beautiful heartbreaking smile.

The girl turned and stepped back to her handmaidens, their hands flapping theatrically in panic and fluster. There was a rustle of cloth behind her and she turned only to find the pit, now empty but for the blood and the cooling dead.

…………………